These charismatic creatures often make people laugh as they appear so clumsy on the land, often slipping over and waddling wherever they go. However as soon as they enter the water it is a very different story! Penguins are extremely elegant, agile and fast swimmers which is vital as they must catch quick swimming prey such as small fish, squid and krill.

The largest penguin species is the Emperor standing at over 1m tall and weighing around 35 kg.

There are around 17-20 species of living penguins. The exact number is debated amongst experts.

The smallest penguin is called the Fairy or Little penguin and stands at only 40cm tall, weighing only 1kg.

When you think of penguins it is probably an icy, snowy scene that springs to mind. However this is only accurate for a few species which are found in the Antarctic. Many penguin species are actually found in very warm parts of the world, living on sandy beaches and rocky outcrops in South Africa, Australia and Chile for example. The Galapagos penguin is even found north of the equator!

It is not surprising then that penguins from different parts of the world have very different adaptations to help them cope with their environment. For example, penguins from warm climates, such as Humboldt penguins from Chile, have pink, featherless patches on their face where they send blood to cool off if they get too warm. In contrast, Emperor penguins, who must survive temperatures down to -40 degrees Celsius have a layer of insulating fat up to 3cm thick to keep them from freezing.

Penguins in South Africa enjoying the sunny beach.

Spot the little pink, bald patch by the eye that helps these warm climate penguins to cool off!

No cooling off required! Penguins in Antarctica are designed to deal with extreme cold.

All penguin species look rather smart, as if they are wearing tuxedoes. However, the colouring and design of their feathery suit is a form of clever camouflage called countershading. Their back is black in colour which helps them to blend in with the dark, ocean depths when viewed swimming from above, however their white belly helps them to blend in with the bright, sunlight ocean surface when viewed swimming from below. Countershading is a very common form of camouflage in the ocean; many sharks have light bellies and dark backs, as do whales, dolphins, fish and many other creatures.

Moulting

Unlike most birds which lose and replace one or two feathers at a time, penguins lose theirs all at once during

what is known as a catastrophic moult. For a week or so they resemble punk rockers with fluffy Mohawks and feathers sticking out all over the place! Penguins don't seem to enjoy this process as it means they cannot swim, but after it's finished they are left with a nice new layer of healthy feathers.

Predation

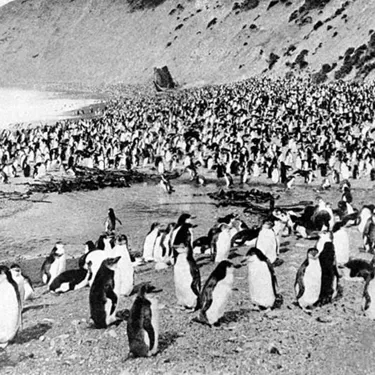

Penguins live is big groups known as colonies which can sometimes contain thousands of birds! Not only does this provide safety in numbers but during the deadly cold Antarctic winters it is vital to survival for penguins to huddle together for warmth.

Antarctic penguins are preyed on by Skuas and Giant Petrols (large predatory birds) when they are chicks but have no land predators once they are adults. In the water however they are preyed on by Leopard seals, sea lions and Killer whales. The first Antarctic explorers were surprised to find that the penguins they encountered had no fear of them; with no land predators adult penguins had not evolved to fear animals they encountered out of the water.

Penguins from warmer climates have to contend with terrestrial predators such as foxes, eagles, snakes and dogs as well as seals, sea lions, Killer whales, sharks and other marine predators too. Small penguins such as Little penguins and Magellanic often build their nests in burrows where they are safer and hidden at night.

Compared to their marine predators, penguins are small, fast and agile. If being chased a penguin will zig-zag and porpoise (jump in and out of the water) to confuse and out-manoeuvre their pursuer. Predators which specialise in catching penguins, such as the Leopard seal, must usually take penguins by surprise to be in with a chance of catching them. Leopard seals often wait at the water's edge to catch penguins as they are first leaping in.

Breeding

Penguins live and breed in large colonies. They form monogamous pairs for the breeding season and sometimes the same pair will recouple again in years to follow, but not always.

Most penguin species lay two eggs in each clutch, but the two largest penguin species, the Emperor and King penguins which are found in Antarctica, only lay one egg at a time. The males and females share parenting duties through from incubation to feeding and protecting their chicks. Incubation shifts can last from days to weeks as they take turns to head out to sea to feed.

A Long Winter

Emperor penguins are the exception to this rule as the male looks after the egg throughout incubation. During the Antarctic winter adult Emperors travel to colonial nesting areas inland from the edge of the pack ice, often travelling over 100km to breed.

As soon as she has laid her egg the female will pass it to her partner and, having used up the last of her nutritional reserves, head back to the ocean for two months to feed. The males are left to incubate their eggs through the dark winter and therefore fast for over 100 days. Males huddle together taking turns in the middle of the group in order to survive the freezing winds of up to 120mph.

When the females finally return they find their mate, among the hundreds of fathers, by recognising their call. Now, well fed and re-energised, it is the females turn to take over caring for the chick, regurgitating food from her stomach to feed it, and the male is free to return to the ocean and finally eat.

(Photo credit: Ian Duffy)

Here at SEA LIFE London our first penguin chick, Elsa, hatched in May 2014. Her parents, Luna and Arnie, were naturals and Elsa quickly grew to a healthy adult size, fast becoming one of the most inquisitive and outgoing members of the colony.

When Elsa was first born she weighed only 90g.

Gentoo Penguins use pebbles to build their nests so when breeding season comes around we make sure they have plenty! The most desirable pebbles regularly get stolen and pass from nest to nest!

Within two months of hatching Elsa weighed nearly 6kg! Young birds grow up fast!

Threats

(Photo credit: Ben Tubby)

Melting Sea Ice

Emperor and Adelie penguins depend on the sea ice for access to food and to breed, so as climate change is melting the sea ice, penguin populations too are disappearing.

Climate Change

Climate change affects water temperature and currents which in turn alters prey distribution for penguin species in many parts of the world, including African penguins. This makes it harder for them…

Overfishing

Overfishing is decimating populations of fish that penguins rely on, and unselective fishing methods mean penguins are caught and drowned in fishing nets as bycatch.

Oil Spills

Oil spills can be particularly devastating for penguin populations. As penguins live in large colonies, a single oil spill can affect a huge number of birds in a short period of time. Oil penetrates…

Plastic pollution

Plastic pollution has found its way to all corners of the earth. Plastic particles are even found in Antarctic waters. Many marine bird species are found to die of starvation after filling their…

Ways you can help!

Meat Free Mondays!

One simple way to reduce your carbon footprint and to help in the fight against climate change is to eat a little less meat. Why not try going meat-free for one or two days a week?

Choose Sustainable Seafood

Look out for the Marine Stewardship Council logo when you're shopping for seafood or eating out!